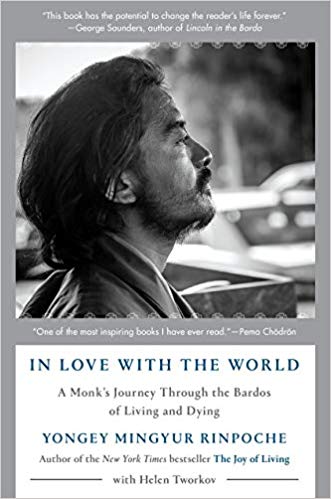

A review of In Love With the World: A Monk’s Journey Through the Bardos of Living and Dying by Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche with Helen Tworkov

Nyogen Roshi strongly recommended this book to me because the author writes in detail about what he does with his mind when faced with fear.

Nyogen Roshi strongly recommended this book to me because the author writes in detail about what he does with his mind when faced with fear.

Mingyur Rinpoche was born into a family of Tibetan Buddhist teachers and recognized as a tulku (reincarnation of a spiritual adept). As such, he trained his entire life in meditation and was groomed to lead his family’s monasteries. He had never traveled alone without a “broad shouldered” monk to protect him, never gone without food or lodging, and never handled money. At age 36, he announced he would begin a three-year retreat. He had done retreats before. What he didn’t tell anyone was that he would do this one alone in the world as a wandering beggar. Thoroughly schooled in Buddhist teachings yet still doubting his realization, he set out to test the power of his practice to overcome fear and shed the attachment to his deeply ingrained identity.

After a nighttime escape from his gated monastery in Bodhgaya, India, he is at once shocked and terrified by the revolting odors, crowds, chaos, and stress of street life. In this realm, his monk’s robes, which once garnered respect and even reverence, are met with indifference. Viewed only as another sadhu, or mendicant, he has entered a world apart from anything he has ever known.

Tibetan Buddhism has many practices designed to recognize and stabilize aspects of mind such as impermanence, gratitude, and compassion. In telling his story, he makes many asides into the teachings and practices he uses, and illustrates how he applies them to calm his mind amid fear, revulsion, and mental turbulence.

He never sought external release. He didn’t try to change his circumstances. The comfort he sought was in detaching from picking and choosing, and calming his mental outlook even as his circumstances worsened. Even though exhausted by heat and hunger, he focused solely on observing his mind, returning to stability, and deepening his awareness. After spending the small amount of money he brought with him, he walked forward into the present, resolved to take whatever came his way.

His first weeks on retreat culminate with nearly dying. Alone and helpless, suffering a severe illness likely caused by eating spoiled food, he struggles with a torturous choice: to seek a way out by trying to call his family for help, or to experience death as the ultimate release of attachments. He became so agonized by the choice that he eventually saw his only recourse was to pacify his mind. He watched his senses dissolve one by one and experienced profound expansion. In the depths of his consciousness, a choice was made to return to life. He attributed it to deep attachments to fulfilling his work as a teacher. His senses slowly returned to his parched and weakened body. Driven by the sensation of thirst, he reached for a water pump. That’s when his mind’s hold on continuous awareness broke, and he lost consciousness.

For me, this was perhaps the most impactful passage in the book. In one instant of reaching away from himself he lost everything, at least for that moment. He woke in a hospital, aware of the experience he’d had but unable to express it. He realized that the judgment and fear that had accompanied him was gone. Instead, he experienced boundless acceptance, spacious awareness, and expansive love. He walked fearlessly out of the hospital to continue his retreat as an itinerant beggar for the next four years.

He closes this account with a line from a letter he had left to encourage his students when he first departed the monastery. “Everything you have ever wanted is right here in this present moment of awareness.” Only now, he knows it to be true.

This book had a profound impact on me. I see myself referencing his example when I become unsure and afraid or worried about my life. The worst we can imagine is usually death, but he goes into it unafraid and finds what he seeks. The seemingly important decisions we torture ourselves with are not the way. Mind is the way. He walks forward through whatever circumstances come.

A glossary at the back of the book gives the literal translation of samsara as “going in circles.” I’ve experienced that for a long time. His example, this practice, is the way out.