A friend asked me to go to New Orleans a couple of months ago. I said no. She was going there for a convention, and we could split the convention hotel rate the week before. I checked the hotels in the area. It was a great rate. I said no. I had always wanted to visit New Orleans. I said no. I checked into the airfare: $220 roundtrip non-stop. I said no.

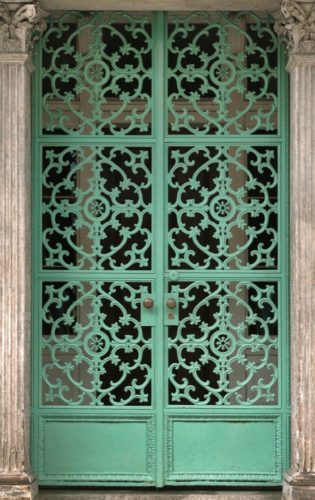

I said no, not out of any reasoned objection or pressing work schedule or financial consideration or any sensible concern whatsoever. I said no because I was just too damn lazy to overcome the obstacles of habit and resistance. I said no because it was easier to say no than yes. I said no because “no” brought a steel gate down on my path and “yes” opened up the road ahead of me.

I said no, not out of any reasoned objection or pressing work schedule or financial consideration or any sensible concern whatsoever. I said no because I was just too damn lazy to overcome the obstacles of habit and resistance. I said no because it was easier to say no than yes. I said no because “no” brought a steel gate down on my path and “yes” opened up the road ahead of me.

Of course I rationalized my decision to say no. The rationalizations always allow me to see myself in a virtuous light, not a hangdog, stick-in-the-mud, defensive light. Somewhere in there, I can usually invoke the starving millions in Africa, the necessity to personally take care of my dog, my plants, my work, when the reality is that the world gets along just fine with or without my supervision.

My Zen teacher tells me all the time that when I see clearly and am present in the moment, all I can see are possibilities, possibilities, possibilities. I like the idea of this. I can see the logic of it. And, to some extent, I actually believe it.

But it’s so much easier to hit the snooze button for another half hour.

It’s so much easier to say no. Possibilities translate to decisions and to work. Seeing clearly may mean seeing things I’d rather not see.

The practice of staying present in the moment without preconceptions or defensive armor is work worth doing. But for me, it’s also work that is hard to sustain and even to remember to do in the first place.

For me, this is the struggle of Zen practice. If I can see an illuminated Exit sign in the dark you can bet I’ll make a dive for it. Show me a shortcut or a way to game the system and I’ll find a way to sell it to myself. I don’t do delayed gratification.

So . . . I just got back from New Orleans. Despite my teacher’s claims to the contrary, I do actually listen to him.

Did I have a good time? Café au lait and beignets twice at Café du Monde; ‘gator tour of the Swampland; Mississippi paddleboat cruise; 21st Amendment bar with incredible jazz; Frenchman’s Street with funky jazz; Bourbon Street with Zydeco; the friendliest people in the world; a town of incredible history and heartache and music.

A day or two into our trip, during one of our stops in an antique shop in Royal Street, I spied a counter of jewelry. I had always wanted a garnet ring, my birthstone. My friend asked if they had garnets. They did. She picked out a lovely square stone set in silver. I said no. It was 50 percent off. I said no. She urged me. It’s beautiful. It suits you. It fits. It’s a great deal. I said no.

A couple of days passed. It was a lovely ring. A half hour before my shuttle was due to pick me up from the hotel to take me to the airport for my flight home, I circled back to the store and bought the ring.

It’s a hard lesson to learn, this saying yes business. It’s also not a mindless kind of affirmation – it’s not saying yes to everything. Lily Tomlin, in the popular TV show “Grace and Frankie,” tries to encourage her friend, Jane Fonda, to take a day to say yes to EVERYTHING. Fonda’s character said she followed that advice, “And that’s how I ended up with a Del Taco franchise.” The kind of saying yes I’m talking about won’t have you ending up with a fast food joint.

It’s more of a Zen yes, opening your heart and your mind.

It’s more like an Improv yes.

Zen practice has a lot in common with Improv.

Years ago I studied with an Improv teacher. She taught me that the first rule of Improv is to say, “Yes and…”

When an Improv player steps into the scene, they must first accept the complete reality of everything that is currently going on, even if they wouldn’t have constructed the scene that way. If a character says they have a broken arm, then they have a broken arm, even if you think the scene would play better with a broken leg. You need to clearly see what’s going on and respond to it without interfering with it.

“Yes and” is an invitation to bring others onto the stage to participate and to add to what’s going on. “Yes and” doesn’t argue, negate or bring into question the shared reality. It’s inclusive, welcoming, open-ended and has the added delicious benefit of leading you down rabbit holes you may not voluntarily squeeze into by yourself.

Possibilities. Possibilities. Possibilities. Zen. Improv. Life. Yes. No. Maybe.

So “yes” I went to New Orleans “and” I had a wonderful time, met amazing people, came back renewed with a zest for life and exploration, and with a wonderment for possibilities around the corner.

What can I say? I’m a work in progress.

It’s a hard lesson to learn, this saying yes business. It’s also not a mindless kind of affirmation – it’s not saying yes to everything. Lily Tomlin, in the popular TV show “Grace and Frankie,” tries to encourage her friend, Jane Fonda, to take